Roman Artillery

Introduction

Warfare in Roman times was ugly and shocking in it's ferocity and the injuries sustained. None more so than in the damage caused to flesh and bone by the machines of the Roman artillery. The weapons the Romans had at their disposal were not actually invented by them. They were adaptations of weapons used by the Greeks. The Romans merely took the designs and improved on them, using the materials and knowledge available to them at that time.

Warfare in Roman times was ugly and shocking in it's ferocity and the injuries sustained. None more so than in the damage caused to flesh and bone by the machines of the Roman artillery. The weapons the Romans had at their disposal were not actually invented by them. They were adaptations of weapons used by the Greeks. The Romans merely took the designs and improved on them, using the materials and knowledge available to them at that time.

Roman artillery came in many shapes and forms, but it was all used with one purpose in mind. To attack enemy strongholds and weaken their defences to make the job of infantry easier. To this end , they used a variety of weapons that we shall be examining in detail.

Siege engines

The British tribes had very limited ways of fighting battles. Their creativity in thinking of new methods of dealing with attacks was virtually non existent. As such they relied upon such tactics as surprise assaults and fortresses built behind man made defences.

The Romans had done their research well and knew of these strategies their opponents employed and though of ways to counter them.

So the Romans developed methods of combating the defences of their enemies. First they would lay down a barrage of artillery fire to soften the enemy ready for the military. When the opposition were suitably weakened, the infantry would enter the battle and complete the job

Even today in conflicts such as the Gulf Wars and Afghanistan, these same methods were used to subdue the enemy forces, ready for the foot soldiers.

The ballista.

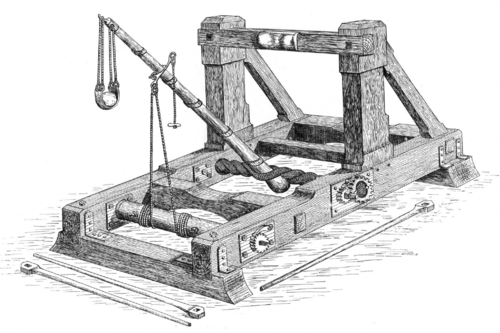

In terrain such as found in Britain, the larger catapult and slingshot type weapons were too cumbersome and heavy to transport to a battle site. So the Romans invented a smaller, easily conveyed, effective weapon. The ballista, which was basically a giant crossbow and indeed developed on the same principle of firing iron tipped bolts towards the enemy positions.

In terrain such as found in Britain, the larger catapult and slingshot type weapons were too cumbersome and heavy to transport to a battle site. So the Romans invented a smaller, easily conveyed, effective weapon. The ballista, which was basically a giant crossbow and indeed developed on the same principle of firing iron tipped bolts towards the enemy positions.

This was a smaller weapon than the catapult type of artillery that fired huge rocks into enemy positions and destroyed the walls so the infantry could gain entry. The ballista was used to kill and injure the people within the fort, rather than damage the surrounding walls.

The construction of the ballista was similar to the Roman bow. The flexible arms that projected from each side at the front were made from layers of thin wood strips. These layers were constructed in such a way that the grain of the wood in a layer was at an angle to the layers on either side. If you have ever seen plywood, you will know the principle. These strips were then glued together to form a flexible yet strong weapon. From the end of each end strands of twisted or platted rope hung loosely. This rope would be pulled back by an artillery soldier using a winch fitted to the weapon. Because of the huge forces involved, a winch had to be employed as no human could ever pull back the rope by hand alone.

The rope was then secured by a locking shaft at the back of the ballista. A bolt or large stone was placed in front of the rope and a length of strong cord attached to the shaft was pulled to release the missile.

The ballista came in a range of sizes with arms anywhere from 2ft to 4ft (60cm to 120cm). Using reconstructed small baliistae, a 1 pound (½ kg) missile could be fired at least 300 yards (275m). The larger ballista was capable of hitting a wall up to 550 yards (503m) away. This was far outside the range of enemy bowmen who could only fire the arrows to a distance of about 110 yards (100m)

The ballista was brought to a predetermined distance from the target. It was loaded with a 3ft (100cm) bolt or a large stone and aimed just above the walls. It was then fired with deadly effect.

The projectile would either hit an enemy warrior, or land in the compound impacting on anyone in the way. The speed of the missile was phenomenal. When it arrived at the target it was usually traveling at about 115mph (184kph). Anyone in the way would not have stood a chance. A bolt would have gone straight through a human body or impaled the victim against a wall. Even if it hit a limb, whoever was hit would have been disabled or even had their arm or leg bone shattered. The rocks fired would certainly have taken off a head without any problem. If they hit someone, the effect was horrific with the body ripped apart and the internal organs splattered for yards around.

The repeating ballista

Roman technicians developed the repeating ballista. A cam was used to move a magazine of bolts , one at a time, into position and also tensioned the rope that fired the bolts. This was very much like a Gatling gun used in the American west of the late 19th century. It was a most fearsome weapon, but not so practical as the lesser machine. This was due to the nature of the machine that caused the bolts to land in a close target area. It could not easily be moved a few degrees between shots as the single shot version could.

This Celtic warrior would have been in agony with a ballista bolt lodged in his spine. His torment would have been ended by a Roman sword |

This Celt would probably never have known he had been hit by a ballista bolt. Note the lack of cracks around the entry point. Such was the speed of impact, it cut a neat square hole in his skull |

The onager (Wild Ass)

This weapon was not as popular in Roman Britain as it was on the continent. This is because it was a very large cumbersome instrument and difficult to transport across the British landscape. Also, it had a much shorter range than the ballista and so had to be deployed closer to the target, often within range of the enemy's archers.

This weapon was not as popular in Roman Britain as it was on the continent. This is because it was a very large cumbersome instrument and difficult to transport across the British landscape. Also, it had a much shorter range than the ballista and so had to be deployed closer to the target, often within range of the enemy's archers.

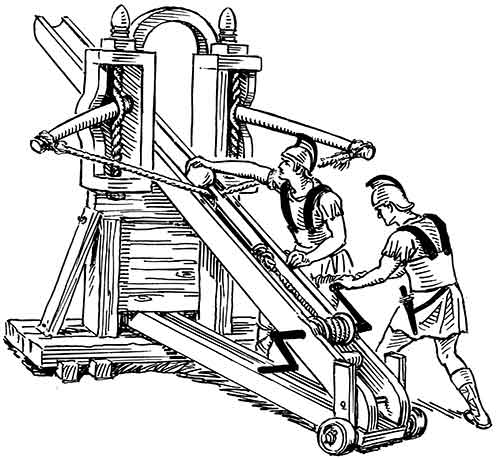

The onager was a base frame with wheels at each cornet. In the middle was a vertical framework with a crossbar at the top. At the bottom was a long beam of wood which was attached at the lower end to a very tightly twisted platted rope. This was to give the spring action to the weapon. At the other end of the arm was a large spoon like container that held the missile, which was normally filled with a heavy rock or masses of stones. The rocks could weigh up to 150lbs (()68kgs) and were used to smash through walls, ramparts and turrets.

In use the onager would have the spoon wound down to ground level and secured by a catch at the bottom. The rock(s) would be loaded and the catch released. The arm would then swing up and hit the crossbar, sending it's deadly cargo towards the enemy position.

Josephus, the writer describes the onager in action.

The momentum of the stones hurled by the engine carried away battlements and knocked off corners of towers. There was a constant thudding of dead bodies as they were thrown one after another from the rampart.

A note: I saw one of these things shot at a Roman Days event. It was crazy dangerous. A HUGE amount of power released and if anything went wrong, you did not want to be near it. I found it way scarier than the 15' high ballista that a reenactor had made (I wonder what ever happened to that?!).

scorpio (Scorpion)

The scorpio or scorpion was type of Roman artillery piece. Also known by the name of the "triggerfish", it was described in detail by Vitruvius. In the progressive evolution of catapults, the next major improvement after the scorpio was the cheiroballistra. A weapon of remarkable precision and power, the scorpio was particularly dreaded by the enemies of the Roman Empire.

The scorpio or scorpion was type of Roman artillery piece. Also known by the name of the "triggerfish", it was described in detail by Vitruvius. In the progressive evolution of catapults, the next major improvement after the scorpio was the cheiroballistra. A weapon of remarkable precision and power, the scorpio was particularly dreaded by the enemies of the Roman Empire.

Design

The scorpio was a smaller catapult-type weapon, more of a sniper weapon than a siege engine, being operated by only one man. The scorpio was basically a primitive giant crossbow, a "catapult with bolts", probably first invented by the Greeks, then later adopted and used on a larger scale by the Roman legions. This catapult used a system of torsion springs, making it possible to obtain very great power and thus a high speed of ejection for the bolts.

The complexity of construction, adjustment and the great sensitivity to any variation in temperature or moisture limited their use, due to the torsion spring which the Romans referred to as tormenta. Moreover, this type of technology, which disappeared as of the High Middle Ages (with the exception of the Byzantine Empire), reappeared during the First Crusade with a new type of catapult based on a system of slings and counterweights which gave rise to the precision balances for the projection of stone balls or giant crossbows (thanks to the progress made in the field of metallurgy).

The first bolt-shooting catapult on display at the Roman Army Museum is the original Greek design, the scorpio, with a front frame made of wood reinforced with metal plates. It first appears in about 350 BC and may have been invented by Greek engineers working for King Philip II of Macedon, the father of Alexander the Great. It was eventually adopted by the Roman army.

The Roman Army Museum's full-size reconstruction is the most authentic made so far because it is a millimetre accurate reconstruction of an actual frame discovered at Xanten-Wardt in north west Germany in 1999.

Actual Scorpio Minor found in the Rhine River

The Xanten-Wardt frame dates from the middle of the 1st century AD, the time of the Roman invasion of Britain. It is no surprise that the iron heads of bolts from this size of bolt-shooter are found at the Iron Age hillforts of Maiden Castle, Hod Hill and Ham hill, three of the British strongholds captured by Vespasian at the start of the invasion in AD 43. The two bolt heads below are from Hod Hill and are on display in the British Museum.

Reproduction Scorpio and relic bolts

The exact sizes of all other parts, the curved arms, stock and stand, are given in the description by Vitruvius, the engineer appointed in charge of the Roman army's catapults by Emperor Augustus.

This design of bolt-shooter continued in use into the 2nd century AD. Two partially completed parts from the wood frame were discovered in a Roman workshop or store, dated to about AD 140, in the 1999 excavations in front of Carlisle Castle.

Use

During the Roman Republic and early empire eras, 60 scorpio per legion was the standard, or one for every centuria. The scorpio had mainly two functions in a legion: in tended shooting, it was a weapon of marksmanship capable of cutting down any foe within a distance of 100 meters. During the siege of Avaricum in the war against the Gauls, Julius Caesar describes the terrifying precision of the scorpio. In parabolic shooting, the range is greater, with distances up to 400 meters, the firing rate is higher (3 to 4 shots per minute) but the precision is significantly less.

Scorpio were typically used in an artillery battery at the top of a hill or other high ground, the side of which was protected by the main body of the legion. In this case, there are 60 scorpio present which can fire up to 240 bolts per minute at the enemy army. The weight and speed of a bolt was sufficient to pierce enemy shields, and usually also sufficient to wound (or outright kill) the warriors who opposed them.